With new generative AI tools releasing every day, the internet is being flooded with content at a rate we have never seen before.

This presents a problem to search engines like Google. Indexing and storing content costs money and resources.

Even before the worldwide adoption of generative AI, Google couldn’t just index every page in existence. Not only did it cost money and resources, but not every page was useful either.

That is even more true today, and Google has been getting more selective as a result.

I’m going to share a simple concept you can adopt to ensure content gets indexed that may be otherwise troublesome.

The overall theme of this concept is that I want to show Google which pages I think are important. If they are important to me and to my site, then that can be a signal to Google that they are worth indexing.

Let’s dive in.

TL;DR – we are going to build internal links

We can argue all day about if links are as important as they used to be, but there is no doubt that links are still a significant factor across Google’s algorithms.

That’s not just for rankings either.

Links also play a role in helping search engines to identify if your content is worth indexing or not.

We all know the role external links play in helping Google to identify important content, but your internal links play a bigger role than you may realize too.

For example, outside of very new sites, you will almost never find a site with a page linked to in its navigation that is not indexed.

Why is that?

Because search engines like Google know that a site’s most important content will usually be found in the navigation.

It’s not just your navigation though.

Improving your internal linking throughout a site can improve your indexing.

Of course you want to make sure blog content is linking to other relevant pages, especially pages you want indexed, whenever possible.

But what else can you do?

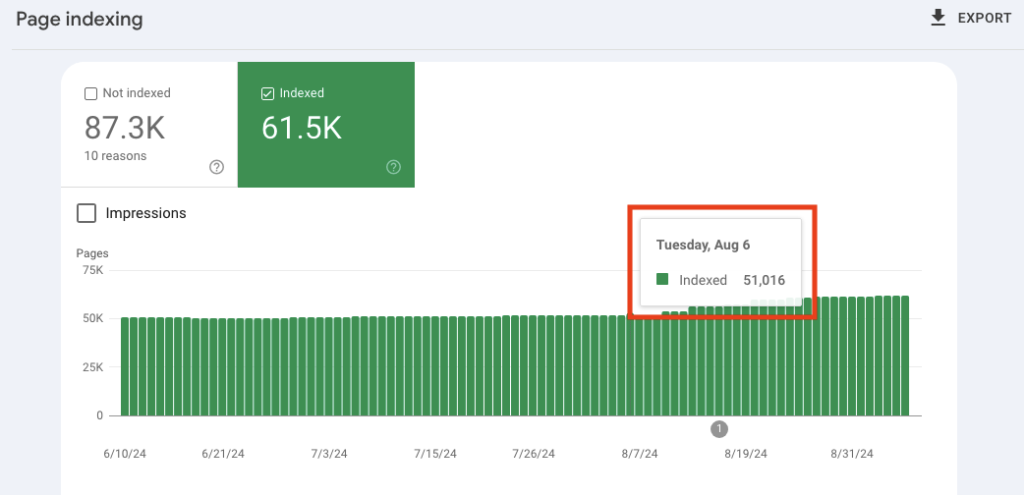

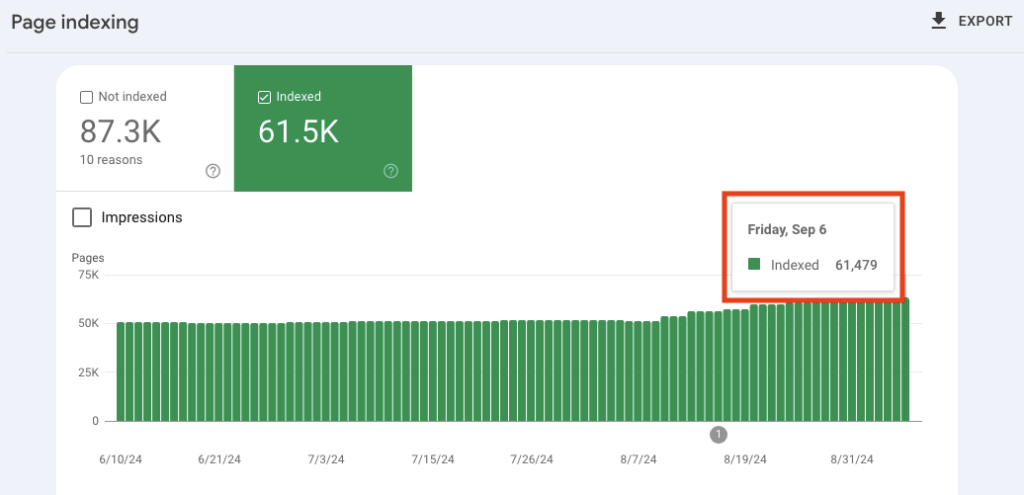

I started working with a site about two months ago that was struggling to get pages indexed. They had about 20,000 location pages for their worldwide services that were not being indexed. This is a site in the travel niche.

One thing that was painfully obvious on this page right away was that they were not linking to these location pages in any meaningful way. They had a Locations page that did link to the landing pages for their most popular cities.

The rest of these location pages were sporadically linked to in blog content when they could, but they didn’t have enough blog content to link to 20,000 different locations.

They really didn’t see themselves publishing enough content on their blog to do that, and even if they did, they likely would have faced a similar struggle in getting all that blog content to index as well.

All of their location pages are a part of their XML sitemaps, but many times that is not enough to get content indexed.

So the first thing we did was build out a series of HTML sitemaps. I’ve shared past notes on HTML sitemaps, and will include a few links here.

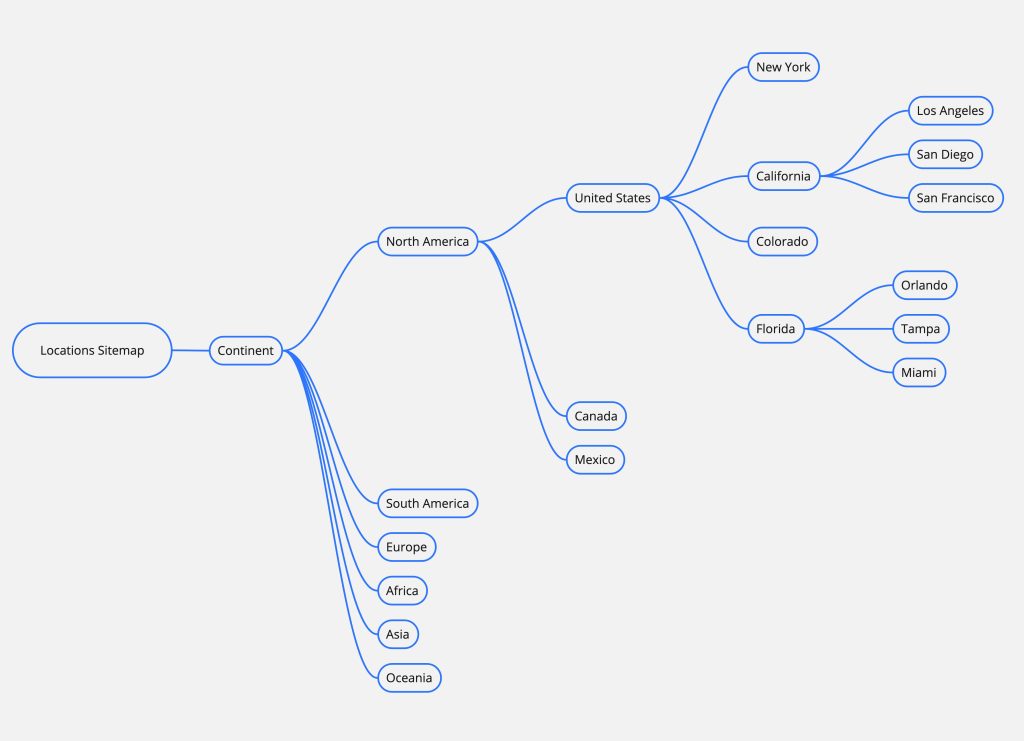

We built one for locations first. We didn’t just throw 20,000 links onto a page. We broke this up into a series of pages. The top hierarchy was countries. Then it broke down from there. For example, in the United States it went Country >> States >> Cities.

Here is the concept map we used to get started on planning this structure. Each node was its own page (an HTML sitemap page) up until the final pages which were the location pages we were targeting.

We didn’t stop there though. We brainstormed together other ways we could slice up and categorize these locations. We created a series of sitemaps that covered things like popular vacation destinations with tropical climates, popular historical vacation spots, best places to vacation for skiing enthusiasts, etc.

At the end of the day we created a small network of pages that were linking to many of these location pages. Like a collection of directories of the site content. The entry to these HTML sitemaps were all linked to in the footer across the site. When appropriate, we also linked to them throughout the content of the site.

The result so far is an additional 10,000+ pages have been indexed in less than a month, and I expect this number to keep climbing.

Improve your crawl depth

Another reason this works is because it improves the crawl depth of the site.

Unless your site is a massive authority like CNN, Amazon, etc. you cannot afford to have your pages buried deep on your site.

For those not familiar, crawl depth refers to how many links from the home page a visitor would have to click on to reach a page. If the shortest path to reach a page involves 6 clicks, you would say its crawl depth is 6.

A good rule of thumb is to make sure every page on your site is reachable within 3 clicks.

This is not always feasible or even possible on really large sites, but if you keep this in mind whenever you publish new content and try to build internal links that keep your crawl depth to a minimum, that will help increase the likelihood your content gets indexed.

If a page is buried 10 clicks deep on a site, what kind of signal do you think that sends to Google about its importance? Is worth indexing, much less ranking?

Again, larger sites like CNN and Amazon can get away with deeper crawl depths because they have much more authority to work with. Most of us are not working with sites that have that kind of authority every day.

If you have ever used a tool like JetOctopus to analyze server logs and see how Google is crawling your site, you will definitely find a correlation between crawl depth and crawl rate and indexation. The deeper within a site you find a page, the less often it will be crawled and less likely it will be indexed.

This was another effect creating our HTML sitemaps in the above example. Some of these location pages were deep in the site. Some you couldn’t even trace a path from the home page to their location. Every page now is just a few clicks from the home page.